INTERVIEW: Which business can be considered successful – profitable, popular, or a unicorn?

Audrius Lučiūnas, entrepreneur, co-founder of Paysera. Photo by DELFI

Over the last few years, we have been hearing more and more about unicorns: something that used to be hard to achieve and almost as if from the world of myths is no longer a novelty in the tech culture. It's no coincidence that in June, Vilnius, also known as the fintech capital, unveiled the "Unicorns" bus stop. But underneath all the glitter and myths lies the reality of business – investors, goals, results, profits or... losses. So what business is considered successful today and how will start-up funding change in the future? In this interview, we discuss this with e-commerce and marketing expert, entrepreneur Audrius Lučiūnas.

- What is your overall assessment of the current start-up funding market?

- The "let's pump up the business, take over the market, and make a profit" start-up mentality that was common 10-15 years ago now has to face the reality – users use the app while it's free, and ditch it when asked to pay for it. Most unicorns are overvalued and investment funds are slowly taking off their rose-tinted glasses, cutting further investments in start-ups.

In order to see whether a company's business model is being monetised, it is not always necessary to attract investors’ millions. If the business model is sound, the business can be profitable without asking investors for money, as shown by companies such as Kilo Health or Paysera.

- Just over a decade ago, there were just 14 unicorns in the world. By comparison, last year alone, more than 700 unicorns were "created". Audrius, what is the reason for the growing number of unicorns in general?

- The main reason is the significant increase in investment. Between 2020 and 2021, the amount of money invested in the US and Europe has doubled or even tripled. However, there is another interesting trend: the number of start-ups receiving investments has not doubled. This means that essentially the same companies are being invested in.

This inflates their value, even without positive financial results. That is why we have lots of unicorns. However, studies and as many as 91% of venture capital funds claim that most unicorns are overvalued. So are all unicorns really unicorns?

"When it comes to growing unicorns, the focus is on increasing the consumer base, and there is only a theoretical model of how it will be turned into value. Once start-ups try to put their business model into practice, it often turns out that it does not work."

– Audrius Lučiūnas

– Audrius Lučiūnas

- Among the unicorns there are not only global companies such as Netflix, Spotify, Uber, SpaceX, Klarna, but also Lithuanian Vinted and Nord Security. However, only a minority of unicorns manage to monetise their activities. The majority of companies are "inflating" revenues at a loss. Why are the majority of unicorns not profitable, at least for the time being?

- Developing unicorns is based on old marketing principles. And one of them is that the market leader takes most of the revenue. And this is true, but there is one additional condition – the company must have a working business model. As start-ups grow rapidly, this condition is often ignored. The focus is only on increasing the consumer base, and there is only a theoretical model of how it will be turned into value. Once start-ups try to put their business model into practice, it often does not work.

And there are many reasons for this. From the fact that consumers are only happy to use a product when it is free, to political instability. In such cases, attempts are made to change the business model, find other sources of income, etc. While there are still no profits, more and more investment is needed to keep the business running. This pressure leads to further investment, which creates a supposed unicorn. This is how it all works. Everything is fine as long as the user base grows, there is the hope of a viable business model, and someone is still investing in it. But when one of these things stops, there comes the sunset of the start-up, regardless of its former perceived value.

- Are there any limits to investment funds' patience regarding unicorn losses?

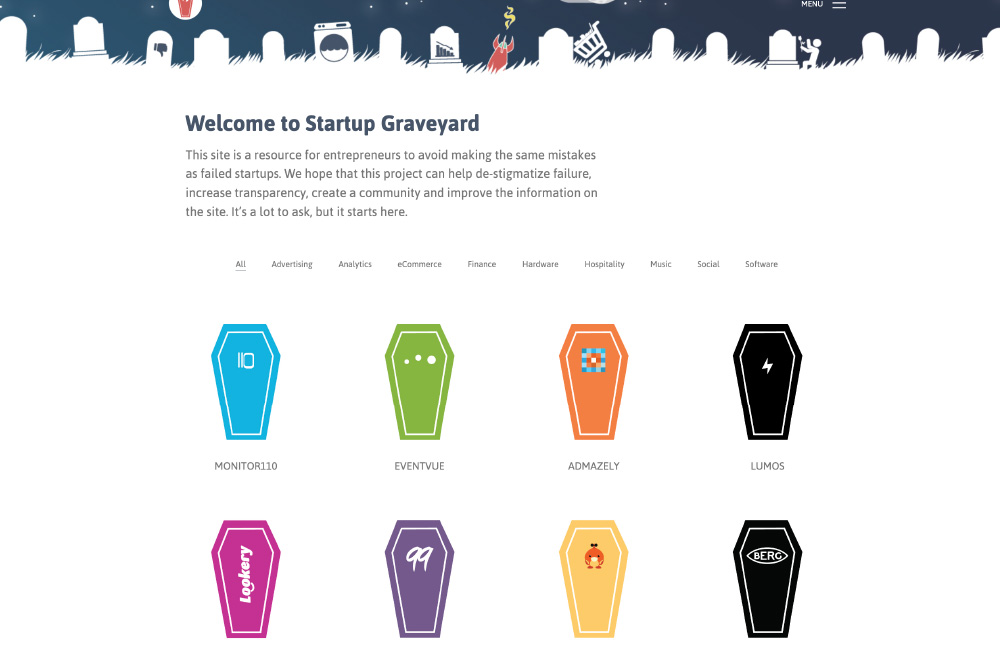

Such exits are as common as investing in a start-up, but hardly anyone talks about them. You would be surprised to know how many such start-ups, potential unicorns, have been shut down by Google or Amazon after being acquired. There is even a virtual graveyard for them on the Internet.

- The investment and financial communities are debating what is the true value of a company. There are two sides of opinion. Those who advocate balance sheet value often calculate the value in terms of the P/E ratio (price to earnings per share). Funds investing in start-ups are more likely to rely on future projections rather than on financial accounting. Which calculation is more efficient?

- How would you suggest calculating the value of a start-up? On the stock market, the price of a share is essentially determined by the type of stock buyers that dominate at the time. Short-term or long-term.

The long-term ones make calculations, analyses, forecasts and buy shares based on them. Short-term investors do not care about all this because they rely on speculation and promises. Therefore, the ultimate criteria for them is that the price of the share they buy today is higher tomorrow. And the long-term investor's technical analysis on its true value does not matter.

According to this approach, at a given point in time, both long-term and short-term investors may be right while holding completely opposing views. It all depends on attitude and expectations.

I would apply the same principle to the evaluation of start-ups. Therefore, there is no single right way to evaluate a start-up, because it depends on the growth stage of the start-up, the market or the expectations of investors, and, for example, whether you want to sell it now, in a year, in 20 years, or not sell it at all. There are many different factors and no one has a crystal ball to predict the future.

For most investors, as for short-term investors in the stock market, what matters the most is that the start-up does well and grows in value until they exit the investment. Whether that value is genuine, how the start-up will develop and what will happen to it afterwards is a question for future investors.

"For most investors, what matters the most is that the start-up does well and grows in value until they exit the investment. Whether that value is genuine, how the start-up will develop and what happens to it afterwards is a question for future investors."

– Audrius Lučiūnas

– Audrius Lučiūnas

- Your businesses – Paysera, Geri lęšiai, Zynky – seem to have no external investors. How are they being funded? Is the money they earn sufficient for their development? Do you borrow from banks?

- I have had both successful and unsuccessful businesses during my career. I have been both an investor and an investment seeker. And each situation is different because it depends on the type of business, its growth potential, profitability, size, etc.

For example, the Zynky opticians' business model took several years to develop. We experimented with different-sized stores in different parts of the city, testing how their profitability differs when operating in a large shopping centre or a residential area, changing the assortment, communication, pricing, etc. All of this was financed by money generated from other activities. However, today this business model is ready for expansion and I am looking for an external investment of such a size that we can continue to open at least one new optician's shop per month in any EU country from the earnings we generate, without further external investment. A year later, 2 new opticians a month, a year after that, 4, and so on, all of them profitable from the very first year of operation. All of this has taken time to implement, but today it would take a relatively small investment to make the whole business a pretty big player on the whole European market.

For example, the investment in Paysera at the time was 10 000 LTL. That was enough to build the company up to what it is today (worth ~ 80-100 million EUR). In today's context, an investment of that size sounds incredible, but it is a key attribute of entrepreneurial ventures. They see opportunities everywhere and they don't need a lot of money to make them happen. Is Paysera the only one? Of course not. Look at what Kilo Group (Kilo Health) is doing right now without major external investment.

- Would you invest in a loss-making start-up? What would the circumstances be? Or would you only invest in a profitable business?

- I am not just a balance sheet value supporter, but I do not like speculating and predicting the future. That is why I avoid businesses where there is a lot of talk about a bright future and no hard data to back it up.

The business model of a company is always important to me. Does it work? How easily do customers spend money on the company's product? Who pays that money and who consumes the product? What is it about the product that makes you want to pay money for it? How long does it take and how much does it cost to attract one paying customer?

It is certainly not necessary for the entire business to be profitable from day one. I really liked the former Amazon model. When Amazon was in a high-growth phase, every now and then they would slow down and make one quarter of the year profitable. It was as if they were saying, 'hey, look, we are okay, stay calm, your choice to invest in us is the right one, because we can be profitable and our whole business model is working'.

This kind of display is what is badly lacking from some unicorns today. Could it be because all we would see is the air coming out of that inflated unicorn?

At this year's LOGIN 2022 conference, Audrius Lučiūnas spoke on "Unicorn vs. Proficorn: change is coming to start-up finance". This interview was originally published on DELFI news portal.